Miwok Tribe: History and Culture

Published on April 5th 2017 by staff under Tribe Facts

The Miwok ( meaning ‘people’ or ‘person’) are aboriginal members of four Native American tribal groups associated philologically. They originally belonged to the region that we come across as Northern California at present.

Tribe History

The origin of the Miwok Native American Tribe is rather ambiguous. While most believe that the Miwok settlements date back to the migrations from Asia approximately 20,000 years ago over the Bering Strait Bridge, certain sources also mention that the Miwoks were descendants of Siberians who entered California about 3,000 years ago by sea.

Before their run-in with European Americans in 1769, they lived in small groups or tribelets along with domesticated dogs devoid of any centralized political authority.

Anthropologists eventually segregated the Miwoks into four geographically and culturally distinct groups. This includes the Plains and Sierra Miwok, of the Sierra Nevada rivers, San Joaquin and Sacramento Valley, and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta; the Coast Miwok of the Pacific Coast; the Lake Miwok of the Clear Lake basin in Lake County and the Bay Miwok, who resided in the current location of Contra Costa County.

While the future of the tribe was threatened by the invasion of their native lands by miners from various countries during the Gold Rush period, their population was also substantially annihilated by a host of epidemics such as malaria, smallpox, and cholera.

Language

The Miwok Indians spoke in seven dialects belonging to the ‘Moquelumnun’ linguistic group of the Penutian tongue of California.

Today, it is an endangered language as most members of the tribe speak in English, with some of the dialects being already extinct.

Culture

Food

Acorn was their staple food item which they pulverized to make soup, bread, and flour. Besides acorn, their summer diet also consisted of berries, seeds, grains and greens such as milkweed, sheep sorrel, wild pea, and columbine. In winter they thrived on bugs, acorns, nuts and animal meat such as deer, rabbits, geese, beavers, quail and elk, which they often seasoned with salt water or seaweed. Among fish, they preferred salmon, shellfish, trout, sturgeon and a few other varieties found in the valley. Their food also included snakes and grasshoppers.

While women were in charge of gathering berries, beans, greens and acorns, the men were involved in hunting and fishing.

Interestingly, the Indians would say a prayer for the hunted animal to be reborn while cooking its meat.

Storage

They used earthen ovens to cook, sometimes roasting their fish and meat whole on an open fire, whereas for preservation they would sun dry or heat them.

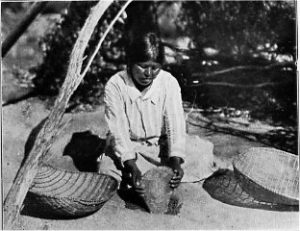

Acorns were stored in round granaries made of grapevines, twigs, brush, and grass.

Clothing

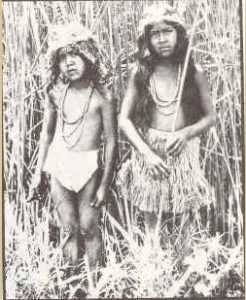

In the summer months, the men wore loin clothes made of deerskin, grass, or fibers of bark. In the winters, they put on leggings, robes, and kilts made out of the hides of animals like wild cats, deer, rabbits, and bear. Though they loved moving barefooted, the tribes would sport high top moccasins while traveling or hunting.

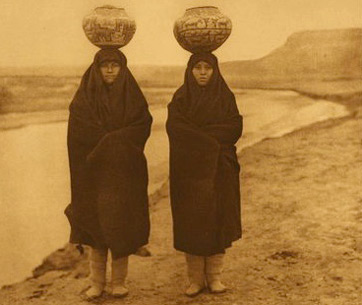

The women dressed in calf-length belted aprons made of willow bark strands or tulle reeds. In some cases, they also wore short skirts made of grass fiber. The Northern Sierra Miwok womenfolk wore wrap-around dresses made of deerskin. During the chilly months, they wore fur or leather robes and woven tule moccasins.

In the colder regions, the women put on buckskin dresses while the men wore deer or buckskin shirts and leggings.

While their attire now comprises of modern clothing like jeans, Miwoks in some parts still wear moccasins.

Jewelry and Accessories

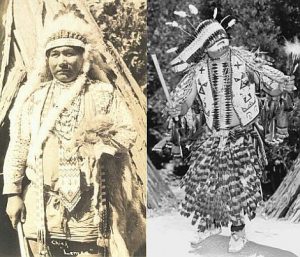

They wore crown-like headdresses for ceremonies. The tie-on headbands consisted of flicker quills of various hues sewn together in a row. Its borders had brown feathers while the hair plumes served as embellishments. Barring special ceremonies, the patriarchal village elders also wore hair nets.

Both the men and women wore jewelry made of shells, beads, feathers and bones on their neck, ear, and nose. They even wore strings with clamshells as necklaces to showcase their wealth. Children wore flower ornaments in their pierced ears and noses.

Tattoo

For special occasions, the male and female folk applied black and white paint and usually had tattoos of three vertical lines running down their bodies, starting at the chin. They obtained the white paint from chalk deposits and the black color from charcoal.

Houses

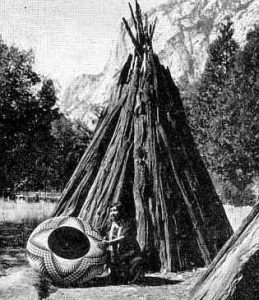

The natives lived in cone-shaped cedar bark or tule shacks, with poles tied together forming a wooden framework covered with tule reed mats and soil. A part of their homes was underground, as they dug out a large cellar under the shacks.

During the winters, they stayed in more permanent shelters made of soil. The roofs having a depth of about 15 feet were hollowed out at the center for ventilation, as well as for smoke to escape from the fire pit. They used ladders to climb out of these shelters.

For special occasions, each clique had their own four feet deep and forty to fifty feet wide assembly house covered with pillars tied together and coated with needles, soil, pine, and brush.

Today, they live in modern houses such as those of contemporary Americans.

Tools and Weapons

They used bows and arrows for hunting; spears, nets (from cord) and strings (of milkweed and hemp fiber) for fishing; and mortar and pestle to crush acorn.

Arts and Music

Miwoks mostly engaged in the art of basketry. They made coiled and twined baskets from willow branches and redbud fibers which they used for carrying water and other objects, to earn rewards or for trading.

In Miwok, music is called ‘kowana,’ where ‘kowa’ means musical bow. Their day to day music consisted of many tunes that they used as love hymns and lullabies.

They carved out musical instruments like bone whistles for dances, an ‘elder whistle’ to cure the sick, the flute, or ‘lula’ played as a pastime or for courtship, as well as a musical bow used mostly by men for pleasure. The male folks were also engaged in making cocoon and clapper rattles, besides foot drums.

Religious Beliefs

Their religion included totem animals with one of the two moieties related to land and water, which they perceived as predecessors of humans. However, according to many of their mythological creation stories, the coyote is not only seen as their ancestor, but also as their creator and trickster god who created the earth and humans out of feather and twigs with the assistance of other animals.

The Miwok people also believed in spirits of humans and animals, considering the latter to be their ancestors.

Miwok Ceremonies

Ceremonies of this Native American tribe comprised of dancing and subterranean assemblies, with a shaman carrying out rites of passage for young girls and boys stepping into adolescence besides preaching the tribe regarding life, conquering fear and overcoming grief.

They conducted the ceremonies in large sweat lodges where the community gathered together adorned in body paint, headdresses, jewelry, and costumes. On such occasions, dance was used as a way to express gratitude for all that they have, appeal for good weather, sufficient harvest and war victories as well as pray for the dead and healing.

In some dances, ‘Wo’chi,’ or clowns painted with white were depicted as coyotes. They also held ‘Uzumati’ or grizzly bear ceremonies wherein the dancer posed as a bear with obsidian claws.

Games and Toys

The children primarily played with toys made of acorn, such as the acorn top as well as the acorn buzzer toy, which is similar to the buzz saw. They also played with whistles, besides toy bows and arrows, which were exclusively used by the boys.

The girls, on the other hand, played with dolls made of soaproot leaves mounted on a stick. They also created a pine needle house for the girls’ dolls.

Some traditional Miwok games were Shinny (a rugby and lacrosse-like sport), Amtup (similar to basketball), football or ‘Po’sko,’ ball race, hoop and pole game, and lance throwing.

Transportation

They molded the canoes, one of their main modes of transportation for crossing rivers, out of large pine logs. They even used rafts for commuting, the Eastern Miwoks using balsa wood or tule rafts.

Though canoes are still in use at present, most of them are seen traveling in cars.

Trade

The four Miwok groups traded principally among each other as well as with the Wappo and Washoe tribes with whom they had friendly ties.

Small clamshell discs with holes in the middle were hung on strings to use as currency. They also used Olivella shells and chips of cylindrical magnesite suspended from strings for trading.

Present Day Status

Government

Currently, the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs recognizes eleven tribes of Miwok lineage in California.

The tribal or general council that operates out of Shippee Lane, Stockton, California, presently regulates the tribal government. The committee holds meetings on the second Thursday of each month, with the elections conducted after every six years.

Membership

Following a controversy regarding the rapidly escalating number of members in the tribe in 2002, the tribe demands a proof of Miwok lineage or ancestry using the ‘blood quantum’ or ‘descent’ system to check the eligibility of the potential member.

In the blood quantum system, the tribe requires individuals to show a Certificate of Degree of Indian Blood (CDIB) or ‘white card’ from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) proving their fulfillment of the tribe’s standard degree of tribal blood (such as half or one-fourth). On the other hand, in the descent system, they must only prove that they are direct descendants of any former Miwok member.

Present Day Settlements

Most Miwoks still live on rancherias or small reservation patches in California. Presently, there are several Miwok reservations including Shingle Springs Rancheria, Sheep Ranch Rancheria, Buena Vista Rancheria, Chicken Ranch Rancheria, Middletown Rancheria, Jackson Rancheria, and so on. Some now live in towns of Northern California, while the others live in intertribal communities alongside members of other tribes, the Round Valley Reservation for instance.

Related Articles

Zuni Tribe: History and Culture

Zuni Tribe: History and Culture

The Zuni are a North American Indian tribe, classified as belonging to one of the nation’s oldest groups, the Pueblo Indians. They call th

Yurok Tribe: Facts, History and Culture

Yurok Tribe: Facts, History and Culture

The Yurok, considered to be the largest Indian tribe of California, inhabited the northwestern region in the areas adjacent to the Klamath R

Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin: Facts, History and Culture

Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin: Facts, History and Culture

The Menominee Indian tribe is a federally recognized Native American group having about 8700 members at present. They had risen to prominen